Introduction

Learning Python is an exciting journey. Its clean syntax, vast ecosystem, and popularity across web development, data-science, automation and beyond make it one of the best beginner languages. Yet even Python beginners fall into common traps. Avoiding these missteps early not only saves time and frustration, but also sets a strong foundation for writing readable, maintainable, and bug-resilient code.

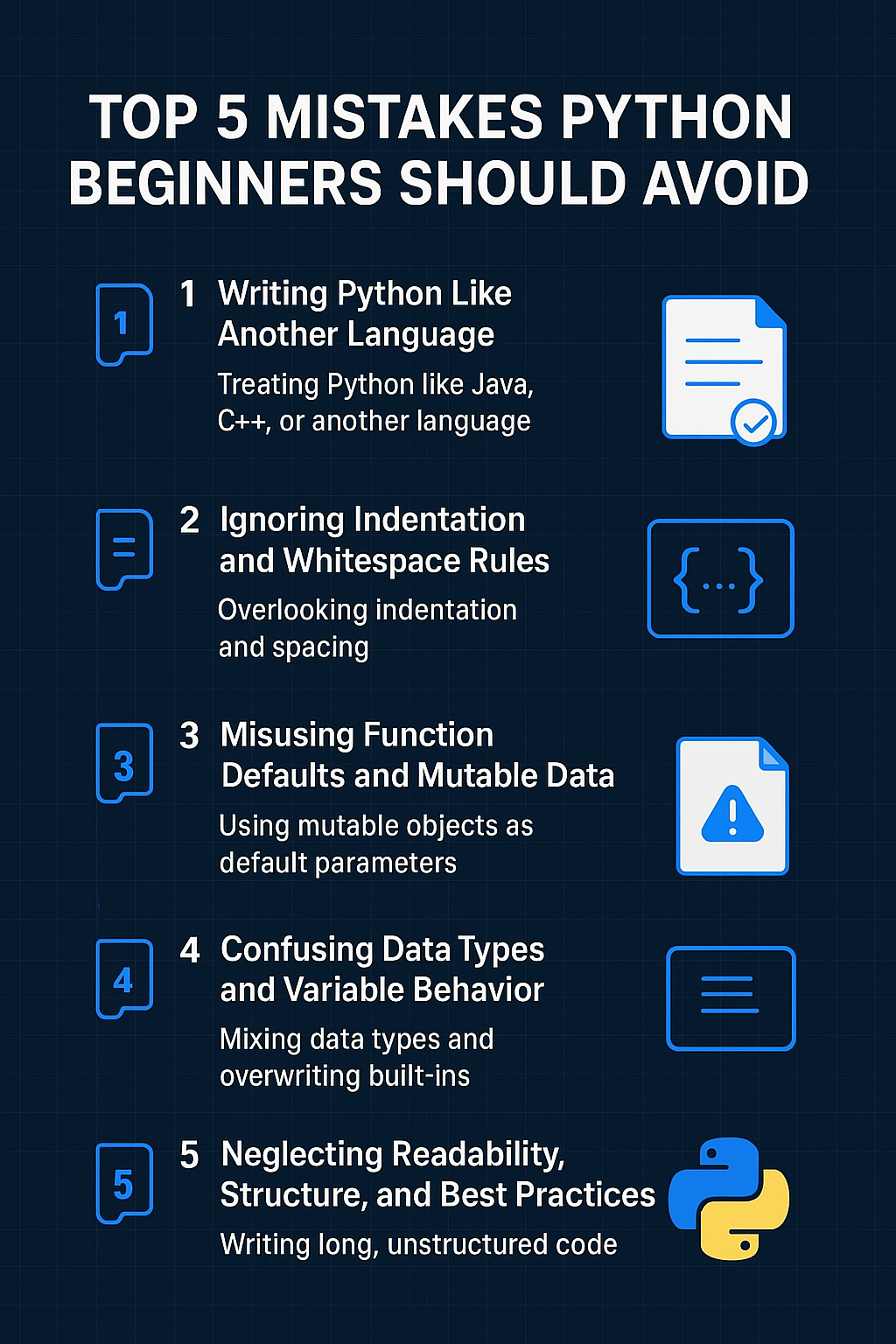

Mistake 1: Treating Python like another language (forcing old habits)

When you come from languages like Java, C++ or C#, it’s very natural to carry over habits — for loops with indices, manual memory management concerns, verbose getters/setters, etc. But Python has its own style and idioms, and trying to force it into another language’s mould often leads to un-Pythonic, clumsy code.

The second version is clearer, more direct, and leverages Python’s iteration features.

Why it matters

Cleaner, more readable code.

Lower chance of off-by-one errors or index mistakes.

Leverages Python’s strengths rather than fighting them.

How to avoid it

Learn Python-specific idioms early: list comprehensions, for-each loops, enumerate(), zip().

Resist the temptation to do “-1” tricks or index arithmetic just because you know how from another language.

Keep readability in mind — the official Python philosophy says “Readability counts”.

Mistake 2: Ignoring the significance of indentation, whitespace, and syntax

In Python, code structure is conveyed by indentation and whitespace. For many beginners used to braces or keywords for scopes, this is a subtle but important shift. Simple things like missing a colon, mixing tabs and spaces, or mis-indentation will cause errors — sometimes confusing ones.

Why it matters

These errors are preventable and can be caught by linters, yet they still trip up many beginners.

Once you’re comfortable with Python’s structure, you’ll spend less time debugging syntax and more time focusing on logic.

How to avoid it

Use a modern editor (VS Code, PyCharm, etc.) with Python support, linting and auto-formatting.

Configure the editor to enforce spaces (e.g., 4 spaces) and avoid mixing tabs.

Always scan your code for missing colons, parentheses, or mismatched indentation blocks before running.

Read and learn from the error message — Python’s tracebacks are your friend.

Mistake 3: Using mutable default arguments (or incorrect function defaults)

This is a classic pitfall unique enough to Python that every beginner should know it. When a function uses a mutable default argument (like a list or dictionary), the same object is reused for every call — often leading to unexpected behaviour.

Why it matters

Unexpected side effects if you assume a fresh list is created each time.

Hard-to-debug bugs — especially when state “leaks” between calls.

It signals a deeper need to understand how Python handles objects, default arguments, references.

How to avoid it

Always default to None when the intended default is a mutable object.

After you gain such awareness, use type annotations (optional) and document behaviour.

Write tests to check edge cases (e.g., repeated calls).

Dive deeper into Python’s object model and default evaluation semantics.

Mistake 4: Not understanding data types, immutability and variable shadowing

Beginners often misunderstand the difference between mutable vs immutable types, how variable assignment works in Python, and the dangers of shadowing built-ins or variables. Some key sub-mistakes include: using lists as dictionary keys, treating strings like arrays incorrectly, or naming variables list, dict, or type, thus hiding built-in behaviours.

Why it matters

Misusing types can lead to exceptions or subtle bugs.

Naming conflicts make later code harder to read and maintain.

Understanding mutable vs immutable is central to correct Python programming.

How to avoid it

Learn the built-in types in Python and their behaviours (list, tuple, dict, set, frozenset).

Avoid using names that clash with built-ins (list, dict, type, str, int, etc.) — check via help() or dir() if unsure.

If you need a copy of a list, explicitly use list.copy() or slicing [:] to avoid referencing the same object.

Use tools like mypy, static type checkers or linters to catch questionable assignments.

Mistake 5: Not leveraging Pythonic practices & ignoring code readability

One of Python’s biggest strengths is its readability and expressive power. Following poor habits leads to code that’s hard to maintain, hard to read, or hard to scale. Common issues include extremely long functions, lack of docstrings, not modularizing code, ignoring naming conventions (PEP 8), skipping testing, and not following the “Zen of Python”.

Why it matters

Readable code is maintainable — one of the core tenets of the Zen of Python.

Modular, well-documented code is easier to test, easier to debug, easier to reuse.

Good habits formed early will serve you when you move from learning scripts to full applications.

How to avoid it

Follow PEP 8 style guidelines: proper naming, spacing, line length.

Break down large functions into smaller ones, each doing a clear job (Single Responsibility Principle).

Write docstrings for modules, classes, functions: what they do, what they expect, what they return.

Use descriptive names: calculate_average_score() instead of calc(); student_records instead of s.

Add basic tests (use built-in unittest or pytest) early — not just for large projects, even for your learning scripts.

Read “import this” in Python and reflect on those guiding principles.

Putting it all together: How to move forward with confidence

Avoiding these five broad categories of mistakes doesn’t guarantee you’ll never miscode — everyone does. But being aware of them means you’ll dodge the most common potholes and develop solid habits.

Here’s a concrete checklist for your next Python project or practice session:

Start small and readable: Write a focused function first, test it, then build up.

Use editor tools: Enable linting, code formatting (Autopep8, Black), and see syntax warnings early.

Write, don’t just watch: Code from tutorials, but then modify, extend, break it — you’ll learn more by doing.

Refactor often: After your code works, take five minutes to clean names, extract helper functions, add docstrings.

Read your error messages: If Python throws an error, use it as a learning opportunity — tracebacks are teaching aids.

Review and reflect: After finishing a mini-project, ask: Did I use mutable defaults? Did I shadow built-ins? Is my code readable?

Build up gradually: Once comfortable, explore modules, classes, tests, typing — but don’t skip the basics.

Conclusion

Starting with Python is more than just writing code that runs. It’s about developing a mindset, habits and practices that will scale as your programming tasks grow. By avoiding the five mistakes outlined above — forcing other-language idioms, ignoring syntax/indentation rules, using mutable defaults, mis-handling types/shadowing and ignoring readability/structure — you’ll accelerate your learning, reduce frustration and write code that others (and future you) will thank you for.

Keep practicing, keep refactoring, and remember: clean, readable, maintainable code isn’t a bonus — it’s the norm in Python. Happy coding!

Tags : .....