How Black Holes in the Early Universe Grew Faster Than Scientists Expected

By sharo charu 27-01-2026 6

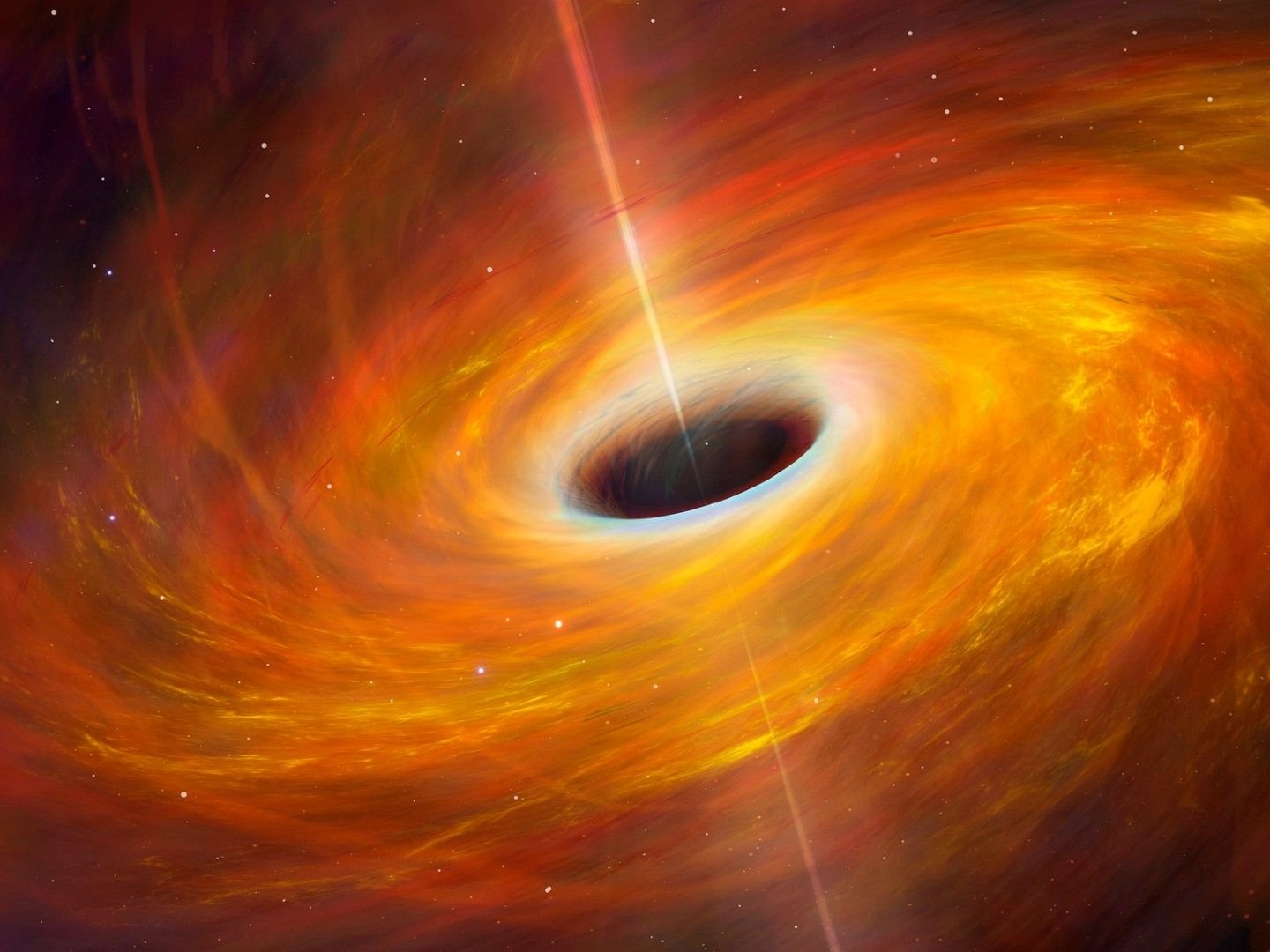

The universe is full of mysteries — and black holes are among the most fascinating. Recently, astronomers have uncovered evidence suggesting that some black holes in the early universe grew at astonishing speeds, much faster than traditional physics would predict.

What’s Happening? The Basics of Black Hole Growth

Black holes grow by pulling in surrounding gas and dust — a process called accretion. As matter falls toward a black hole, it warms up and emits intense light and radiation. This radiation pushes back outward, creating a natural “speed limit” on how fast a black hole can feed. This speed limit is called the Eddington limit.

Under normal conditions, a black hole should not be able to grow faster than this limit. But recent observations suggest that this limit can be broken under the right conditions.

Why It Matters: A Cosmic Puzzle

Astronomers have long struggled to explain how supermassive black holes — ones millions or billions of times more massive than the Sun — formed so quickly in the early universe. Telescopes like the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) have spotted these giants when the universe was less than a billion years old — far sooner than standard models predicted.

This means the black holes must have grown incredibly fast — and the usual rules don’t fully explain how. That’s why scientists are now looking into extreme scenarios where black holes temporarily violated the growth limits imposed by theory.

How It Happens: Super-Eddington Accretion

The most promising idea to explain this rapid growth is called super-Eddington accretion. In simple terms:

- The black hole’s feeding “speed limit” can be exceeded when conditions are right — especially in the chaotic, gas-rich early universe.

- Dense clouds of gas and turbulence in young galaxies may have let black holes gobble up matter quickly, becoming much more massive in a short time.

- In some extreme cases, black holes are observed accreting material at many times the normal limit — for example about 13× faster than the Eddington limit, challenging what we thought was physically possible.

This rapid feeding helps explain how supermassive black holes could reach huge sizes so early in cosmic history.

What Was Found: Observations That Break the Rules

Recently, astronomers using powerful telescopes found a distant quasar — a bright galaxy with an actively feeding black hole — where the black hole appears to be growing at about 13 times the theoretical growth limit.

This discovery highlights that:

- Black holes in the infant universe could grow faster than expected. The standard view of black hole growth (limited by radiation pressure) may not fully apply under extreme early conditions.

- Super-Eddington accretion might be a key part of how the first massive black holes formed.

These unusual observations are still being studied, but they point toward a more dynamic early universe than previously thought.

What Could Happen Next

Astronomers are now looking for more examples of rapid growth black holes to test these ideas. Future observations with telescopes like JWST and the upcoming gravitational wave detectors could help confirm how common these extreme growth episodes were.

If super-Eddington growth was widespread in the young universe, it could reshape scientists’ understanding of:

- How galaxies and black holes co-evolved over time.

- What conditions allowed such dramatic early growth.

- Where the seeds of today’s supermassive black holes came from.

In Summary

Black holes don’t just sit quietly in space — they can grow extraordinarily fast under the right conditions. By studying the early universe and objects like quasars that seem to defy conventional limits, astronomers are uncovering surprising new clues about how the cosmos formed its first giants.